It’s interesting to me that when I first heard of Monte Wolfe and interviewed Harry Schimke, Monte’s unusual life had been covered by the San Francisco newspapers, the Stockton Record, local newspapers and several historical societies. But, no one investigated Monte like Don DeYoung. Don first contacted me about my blog in 2009 and went on from there to meet the Schimke family. Harry’s daughter, Susan had all of her father’s photos and notes, and his brother Art was still alive. Don did a major investigation about Monte that led to a vastly more accurate portrait of Monte than anyone had before. As he put it, thanks to the internet, his skills and his own boyhood fascination with Monte from a boy scout camping trip, (that he describes in one of the links below), Don satisfied a lifetime fascination. Monte disappeared in 1940, a date established by Harry Schimke, who was the last person to see him alive.

Mark Bonar, too, became fascinated by Monte as a young man through his father-in-law, Paul La Teer, and subsequently collected materials, visited the cabins and introduced his own children to the legend of Monte Wolfe. Monte built the “new” or second cabin in about 1933, Mark is guesstimating. As you can see, the hinged door is missing but the old woodsman’s device for “barring the door” was in place.

Mark told me, “Paul knew that country and used to stash food, sleeping bags and wool blankets in rocks behind Camp Irene, which was about eight to fifteen miles below Monte’s cabins. A Forest Service trail led down to the new cabin from the Blue Lake side. It is located about 12 miles from the mouth of Summit City Canyon Creek. The creek funnels into the Mokelumne. The cabin was well hidden, nestled among the trees about 100 yards from a sharp bend in the river. There was a horse trail leading down behind the cabin (as yet not re-discovered). Monte, too, used “spike” caches to hold food and traps on his forays throughout the steep Sierra Nevadas, a common practice for ranchers chasing cows, sheepherders, trappers, fishermen and hunters.

Mark found a paper at the cabin describing how Monte built that cabin by himself. He hoisted all the material up onto the ridge pole using the wetted incline plane principle. The door was small, but extremely heavy. “The door probably weighed 150 pounds and had massive hinges. No one could remove the door without special tools or help.

“The cabin was beautiful; strongly built, with two rooms. The foundation of lightly charred cedar rounds discouraged insects. He had a screened pantry high up off the floor to keep out mice. Monte dug a fresh spring near the cabin from which he piped water into a carved wooden sink and to a solar shower he hooked up on the cabin’s outside wall.”

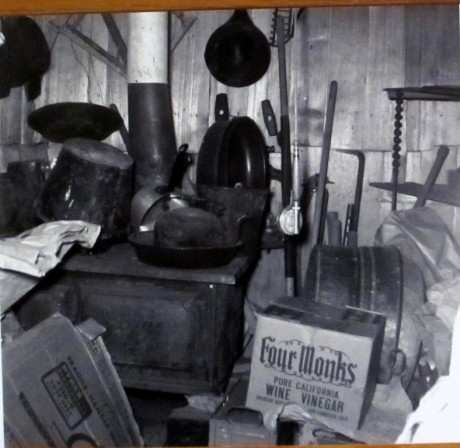

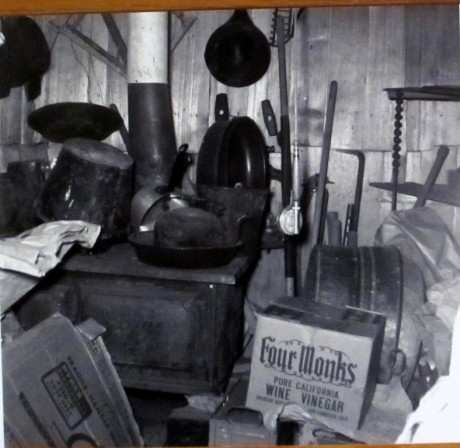

“He also built a partly under-ground smoke house with hooks enough for 100 trout or a large deer cut into pieces.” Mark showed me pictures of carved log chairs, a table and other items Monte made. There were also comfortable furnishings that Monte hauled into that steep canyon from long distances.

(The above two pictures were taken by Mark on one of his many visits to the cabins.)

“Monte hauled a heavy cast iron cooking stove from Hermit valley to the cabin, piece by piece. He was exceptionally strong.”

Monte was reported to throw a canvas sack of nails over his shoulders weighing 80-100 pounds, stand with it on his shoulders and visit for an hour and never set it down, then move on as though carrying nothing. He was seen setting off from Blue Lakes on skis to his cabin on the Moke, at night, an incredible feat in the day time, without the deceptive shadows cast by the moon. Paul Le Teer described him as “…a swarthy, short man; a dead shot with a rifle, small feet, enormous calves, slender waist, and the broad shoulders of an athlete. He wore his long hair in braids, sometimes tied by a ribbon.”

There are many engaging stories of Monte’s exploits. One I heard from a former bartender at Tamarack concerns the romantic Monte. Supposedly no one, the law, nor wardens could “sneak up” on the expert woodsman. But, the Bartender came across him lying in a naked embrace with a woman on a large flat rock in the bright sunshine. He retreated undetected.

After Monte’s disappearance, people began using the upper cabin until the U.S Forest Service burned it down. The main cabin was harder to find, was locked, and under the “protection” of the Linford family.

Mark has a letter from the Lindford’s to the El Dorado Forest Service Supervisor, Edwin Smith, after Monte’s disappearance was formally acknowledged. The Lindford’s were well off and owned an Oakland Construction Company. They befriended Monte and convinced him to jointly establish a mining claim on Monte’s properties, meaning the area of his cabins and property he occupied, but didn’t own. The Lindord’s enjoyed, with Monte, a private, free, Shangri La Cabin in the mountains. From the letter, Mark speculates the Lindford’s were interested in the amazing private cabin retreat more than Monte. The letter admits that they had never mined nor taken any minerals on their claims, they simply wanted to use the cabin and lands that Monte occupied and asked permission to continue to do so. Permission was granted them as long as they did not extend that privilege to others. So, they shared a special lock with the forest service on the cabin door.

“Between 1955 and 1970, ” explained Mark, “fewer people were going to the cabin. The elder Linfords were essentially gone and their son, family and friends used it on rare visits. A tree fell on the cabin and took out one corner of it and the end result would certainly be steady deterioration. The cabin was repaired much later by a committee of interested people formed to protect the cabin. The non-profit Monte Wolfe Society was formed by James Linford.

The U.S. Forest service decided in recent years that the cabin should be left to deteriorate and removed the door to hurry the process and prevent people from using the cabin. They emptied the place of everything but the stove. The group has taken legal action against that decision, arguing that the Mountain Man’s place is an historical artifact like an Indian Ruins and should be preserved. The group has succeeded thus far in having the door replaced and the chimney pipe hole patched in 2010. That is heart warming progress indeed.

Don DeYoung’s book is still awaiting publication. But, in the meantime, there are several websites about De Young’s extended research, including locating Monte’s grandchildren and learning his real name at the very interesting links below.

http://blogs.esanjoaquin.com/san-joaquin-river-delta/2009/07/28/monte-wolfes-cabin/

http://deyoung.org/MonteWolfe/

http://montewolfe.blogspot.com/

http://www.montewolfe.com/

http://www.recordnet.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20090727/A_NEWS/907270305

Mark Bonar, too, became fascinated by Monte as a young man through his father-in-law, Paul La Teer, and subsequently collected materials, visited the cabins and introduced his own children to the legend of Monte Wolfe. Monte built the “new” or second cabin in about 1933, Mark is guesstimating. As you can see, the hinged door is missing but the old woodsman’s device for “barring the door” was in place.

Mark told me, “Paul knew that country and used to stash food, sleeping bags and wool blankets in rocks behind Camp Irene, which was about eight to fifteen miles below Monte’s cabins. A Forest Service trail led down to the new cabin from the Blue Lake side. It is located about 12 miles from the mouth of Summit City Canyon Creek. The creek funnels into the Mokelumne. The cabin was well hidden, nestled among the trees about 100 yards from a sharp bend in the river. There was a horse trail leading down behind the cabin (as yet not re-discovered). Monte, too, used “spike” caches to hold food and traps on his forays throughout the steep Sierra Nevadas, a common practice for ranchers chasing cows, sheepherders, trappers, fishermen and hunters.

Mark found a paper at the cabin describing how Monte built that cabin by himself. He hoisted all the material up onto the ridge pole using the wetted incline plane principle. The door was small, but extremely heavy. “The door probably weighed 150 pounds and had massive hinges. No one could remove the door without special tools or help.

“The cabin was beautiful; strongly built, with two rooms. The foundation of lightly charred cedar rounds discouraged insects. He had a screened pantry high up off the floor to keep out mice. Monte dug a fresh spring near the cabin from which he piped water into a carved wooden sink and to a solar shower he hooked up on the cabin’s outside wall.”

“He also built a partly under-ground smoke house with hooks enough for 100 trout or a large deer cut into pieces.” Mark showed me pictures of carved log chairs, a table and other items Monte made. There were also comfortable furnishings that Monte hauled into that steep canyon from long distances.

(The above two pictures were taken by Mark on one of his many visits to the cabins.)

“Monte hauled a heavy cast iron cooking stove from Hermit valley to the cabin, piece by piece. He was exceptionally strong.”

Monte was reported to throw a canvas sack of nails over his shoulders weighing 80-100 pounds, stand with it on his shoulders and visit for an hour and never set it down, then move on as though carrying nothing. He was seen setting off from Blue Lakes on skis to his cabin on the Moke, at night, an incredible feat in the day time, without the deceptive shadows cast by the moon. Paul Le Teer described him as “…a swarthy, short man; a dead shot with a rifle, small feet, enormous calves, slender waist, and the broad shoulders of an athlete. He wore his long hair in braids, sometimes tied by a ribbon.”

There are many engaging stories of Monte’s exploits. One I heard from a former bartender at Tamarack concerns the romantic Monte. Supposedly no one, the law, nor wardens could “sneak up” on the expert woodsman. But, the Bartender came across him lying in a naked embrace with a woman on a large flat rock in the bright sunshine. He retreated undetected.

After Monte’s disappearance, people began using the upper cabin until the U.S Forest Service burned it down. The main cabin was harder to find, was locked, and under the “protection” of the Linford family.

Mark has a letter from the Lindford’s to the El Dorado Forest Service Supervisor, Edwin Smith, after Monte’s disappearance was formally acknowledged. The Lindford’s were well off and owned an Oakland Construction Company. They befriended Monte and convinced him to jointly establish a mining claim on Monte’s properties, meaning the area of his cabins and property he occupied, but didn’t own. The Lindord’s enjoyed, with Monte, a private, free, Shangri La Cabin in the mountains. From the letter, Mark speculates the Lindford’s were interested in the amazing private cabin retreat more than Monte. The letter admits that they had never mined nor taken any minerals on their claims, they simply wanted to use the cabin and lands that Monte occupied and asked permission to continue to do so. Permission was granted them as long as they did not extend that privilege to others. So, they shared a special lock with the forest service on the cabin door.

“Between 1955 and 1970, ” explained Mark, “fewer people were going to the cabin. The elder Linfords were essentially gone and their son, family and friends used it on rare visits. A tree fell on the cabin and took out one corner of it and the end result would certainly be steady deterioration. The cabin was repaired much later by a committee of interested people formed to protect the cabin. The non-profit Monte Wolfe Society was formed by James Linford.

The U.S. Forest service decided in recent years that the cabin should be left to deteriorate and removed the door to hurry the process and prevent people from using the cabin. They emptied the place of everything but the stove. The group has taken legal action against that decision, arguing that the Mountain Man’s place is an historical artifact like an Indian Ruins and should be preserved. The group has succeeded thus far in having the door replaced and the chimney pipe hole patched in 2010. That is heart warming progress indeed.

Don DeYoung’s book is still awaiting publication. But, in the meantime, there are several websites about De Young’s extended research, including locating Monte’s grandchildren and learning his real name at the very interesting links below.

http://blogs.esanjoaquin.com/san-joaquin-river-delta/2009/07/28/monte-wolfes-cabin/

http://deyoung.org/MonteWolfe/

http://montewolfe.blogspot.com/

http://www.montewolfe.com/

http://www.recordnet.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20090727/A_NEWS/907270305

3 comments:

golden goose

paul george

supreme hoodie

moncler

jordan 11

stephen curry shoes

pg 1

hermes handbags

curry 7 sour patch

goyard handbags

replica bags philippines replica bags manila replica bags ru

go to website link blog link check that important source their explanation

Post a Comment