Varanasi again. This may be overload, but I will only be here once and the culture fascinates me. At the river, we continued watching the bathers. Some soap up, others swim.

There are no rules. If this were the U.S., guards would be making you stand your turn in-line and directing you to go this way or that and keeping order.

.

Thousands of people on this river every day, bathing, and burning and depositing ashes. The government has to dredge ashes and move them out to sea.

Before we leave the boats, we pass the laundry. All that bathing, towels, and a change of clothes.

Untouchables do laundry. Our guide tells us the great fault of their religion is the caste system that designates children born of untouchable parents cannot change their lot. (An excellent book about the fate of an untouchable woman is, "The Space Between Us", by Thrity Umrigar.

On shore, people are setting up for business. In back, on the steps, people eating breakfast.

Long and steep stairs are covered with water during monsoon up to where the railing ends. Cremations move up with the river.

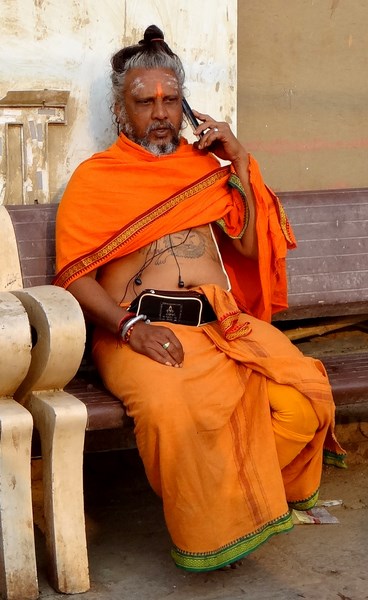

On shore, I see cell phones in use everywhere. In my hometown, in the grand USA, I do not get a dependable signal for a cell phone. I use it from my car when I travel.

A girl hides in the corner, her crippled feet wrapped in rags. A women gives her food. My entire time in India, I never heard a word spoken in anger.

Among the priests, there is no uniform clothing.

And if someone casually sits on your ghat to rest, no one seems to mind.

The priests have various markings on their foreheads, what they stand for I don't know.

Two makeshift barbershops. They shave their heads to honor a loved or maybe to be part of a cremation ceremony.

Those anointed have horizontal or vertical marks. Our guide tells us they indicate something about the person, maybe cast, or what sect they belong to?

A simple gesture, its meaning clear; but there was no hostility or anger because I aimed my camera at him.

The cobra handler's eyes mesmerize, intense.

The musical instrument he plays looks more like a pop gun, but the snake is flared.

Instruments are rudimentary, home-made and for sale. Interesting shapes. They didn't wake up his well fed dogs.

When we arrived in the cold, early morning, this bull was asleep on the steps. Someone anointed him.

We walk back to the bus. Ranvir points out the pilgrims headed for the river are barefoot.

This group of women were laughing and giggling.

I asked what was so funny. It seems one of them had broken her shoe.

Best friends.

Breakfast or lunch is ready.

Hefting their wares closer to the river for sale.

More beggars.

A young father with his son. We reach the parking area and load into the bus.

On the way home, Ranvir asks the bus to slow down so we can see a typical laundry. The main necessity, a steady source of water.

After lunch, some visit a silk rug shop. I was hoping the first rug shop would show the entire process. The removal of the silk worm larvae, winding the fibers, dying the fibers and then weaving rugs. I've seen it before, but Theo has been sleeping a lot and chose to stay in his room.

The bus took us for an afternoon visit to a Buddhist Museum. That next.